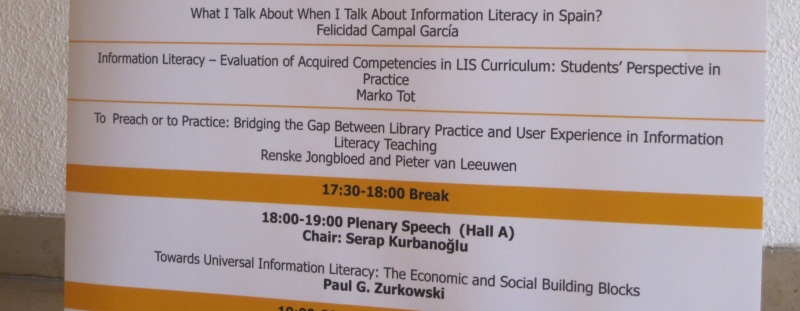

Onze eigen bijdrage bestond uit een PechaKucha, aan het einde van de middag van dag 1. PechaKucha is een interessante maar lastige presentatievorm. Het principe is 20×20: 20 slides die elk precies op 20 seconden geprogrammeerd staan. Improviseren, spelen met het publiek of je verhaal wat uitbreiden is dus onmogelijk, alles moet perfect getimed zijn en lopen als een trein. Na 6 minuten en 40 seconden zijn je slides en tijd onherroepelijk op. PechaKucha’s worden meestal gebruikt om ideeën te pitchen of een discussie los te maken. En dat namen we ter harte.

Met het doel een debat op gang te brengen hebben wij dus op een conferentie over informatievaardigheden de provocatieve vraag opgeworpen of de verantwoordelijkheid voor het ontwikkelen, implementeren en bewaken van een leerlijn informatievaardigheden wel bij Hoger Onderwijs-bibliotheken zou moeten liggen. Wij vinden om diverse redenen van niet (zie de tekst hieronder voor onze argumentatie). Een gewaagde stelling, aangezien ongeveer 90% van de conferentiebezoekers verbonden was aan een UB.

In een gemeenschap die zijn eigen standaarden ontwikkelt, en daarmee de waarde van een zelf-ontwikkeld product bepaalt, is de kans op navelstaren erg groot. Wij zijn van mening dat een organisatie die ondersteunend van aard is altijd haar relevantie voor de gebruikers moet laten prevaleren boven eigen standaarden. Dit impliceert dat het hoe en waarom van wat wij als bibliotheek doen altijd ter discussie kan worden gesteld. Als we dit niet doen, preken we een ideologie, en dat is volgens ons geen goede uitgangspositie voor een organisatie die haar waarde binnen de instelling waar zij aan verbonden is steeds meer moet bewijzen. Vandaar ook de titel van onze presentatie: “To Preach or to Practice”.

Bij dezen per slide de tekst van onze presentatie. De presentatie zelf kun je terugvinden op slideshare (de uitgesproken tekst staat daar in de notes onder elke slide).

We horen graag hoe jullie hierover denken!

To preach or to practice: bridging the gap between library practice and user experience in information literacy teaching

-

Once there was a country called Libraryland. Everybody wanted to come to Libraryland to get access to its vast range of knowledge, its wonderful services and its welcoming people. They only had to enter our Port of Information Literacy, and the rich Pool of Wisdom would be available for them.

-

Too bad though, that this country was only a figment of our imagination. For faculty and students, Libraryland is a small, hidden kingdom. Hard to find, even harder to access. So what explains this difference in perspective? We researched the search behaviour of students and scholars, and distinguish 4 reasons.

-

Reason 1: There is a gap between the needs and goals of students and information literacy teachers. During our research, we noticed that most information literacy teachers struggle to show their value to their students. For them, our value is to satisfy their needs. So what does a student need, according to himself?

-

When we talk about an information need, we think in terms of search strategies, and steps in a process of information retrieval. Students don’t think that way. They want to write their papers and thesises in time, so they just need an article or a book. In short, they want a product, not a process.

-

I don’t know how this is in your countries, but in the Netherlands students get less and less time to finish their studies. This means they focus on speed and not on quality of their output. On the other hand, what are our goals? Drilling them to become “lifelong learners” and active citizens? That’s very noble, but it doesn’t match their goals.

-

Reason 2: Students need to see the added value before they make time to learn a new skill. It is often said by librarians that students badly overestimate their capability to find information, and that their information literacy skills are shockingly poor. Students take the easy way out. But… why shouldn’t they?

-

Ever seen a student search for the cheapest flight to Sydney on a given day? I dare to bet you that they get there faster than we do. Students are willing to learn software and use complex search techniques, if they really need them. But as long as they can complete their studies using Google Scholar, why should they bother?

-

We’ve observed students doing various search tasks, and they’ve all surprised us. They’d probably fail every information literacy test, but also showed us that there are many ways that lead to the right result. They combined blogs, news articles, search engines and their handbooks to locate the sources they needed. And they didn’t need our help with it.

-

Reason 3: What faculties think their students should know is different from what we think students should know. One would expect the goals of information literacy teachers and faculties to be similar, as they are both aimed at educating students to become good scholars. The problem is, that we don’t agree on the skills a good scholar should have.

-

While we tend to think that informtion literacy is an essential part of academic skills, scholars seem to function just fine without it. They have many ways to find literature, like peers, online interest groups and conferences. These have little to do with information literacy, but this doesn’t matter since they are only assessed on the output of their work.

-

As a result, teachers don’t assess the Information Literacy skills of students either. What they test is the understanding of the topic, the manner of argumentation. In a lot of courses, students only have to study the prescribed literature. Even if they do have to search for information, the quality of the search process is almost never a substantial part of the grade.

-

Since there is so much more focus on the result instead of the process, academic skills courses often have to make way for subject specific courses. In this declining window of opportunity, we often have to fight to keep our information literacy courses in the curricula. Let alone get more time.

-

And then we get to the fourth and final reason: we can’t prove our added value. All of us are trained to convince faculties and students that information literacy skills are important, but what are they important for? Do students really need all these skills to complete their studies?

-

Of course, we do measure the impact of our information literacy courses. But these tests only determine the information literacy skills of our students, based on the standards that we created. This is actually a case of circular reasoning: we test the students against our own standards. What we don’t test, is how our courses contribute to study success and higher grades.

-

There are research papers which show a positive correlation between information literacy skills and study results, but correlation does not prove causation. Better study results and better information literacy skills can both be caused by the fact that the tested student was simply smarter or more engaged.

-

University Libraries are a supporting institute. We support students and researchers in doing research and working with our tools. But we’re not an educational institute. Therefore, we propose that us University Libraries stop inventing our own standards, and stop teaching our students information literacy as an ideological learning program.

-

We DO think information literacy is an important matter, but this task should be integrated in primary and secondary education. Libraries should concentrate on what our customers actually need: practical support, specialized knowledge and user-centered services. In short: we should lose our ideology and start thinking like an enterprise.

-

Commercial enterprises adapt their systems to their users, instead of the other way around. If we manage to create a perfect user experience, we don’t even need to give library instructions anymore. And that gives us time to develop other products.

-

Products, such as specialized on-demand services, aimed, for example, at big data analysis, impact measurement or data visualization. It means we have to develop by trial and error, and let go of our darlings. But as soon as we create high quality products and services that address a need, we can stop preaching and start practicing.

-

What this really means, is a different mindset for university libraries: We need to start thinking in terms like cost-benefit and agile product development; We need to take up a pragmatic approach and conduct user-centered market research; And what we really need to do, is to come down from our mountain and step into the real world. Thank you.